In 1930, while talking to the Federal census taker in Dayton, Ohio, Verna’s sister Geneva Miller was recorded as a “clerk at Frigidaire,” while Verna herself was listed as a “stenographer in an office.” Yet company literature shows that Verna had been serving as Frigidaire’s Home Economist Director since 1928, the year before Frigidaire surpassed all manufacturers in unit sales of electric home refrigerators. We’ll discuss Verna L. Miller soon, including her early years in which her mother took the children and escaped to Dayton, Ohio. Yet, first, if you wish, read in the link about the invention of home refrigerators. The primary objective of Frigidaire at first was to find new consumers who still used ice boxes and persuade them to choose Frigidaire for their first electric refrigerator.

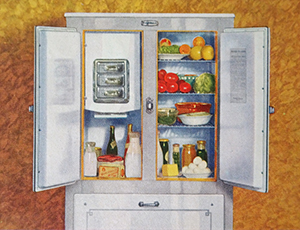

Beginning in 1928, Verna educated homemakers to the benefits of Frigidaire’s refrigerators through talks and food demonstrations at clubs, colleges, and beyond. She created and tested recipes for Frigidaire’s cooking booklets, and had the recipes retested in hundreds of homes. Some of the benefits she professed in her communications were: Although the upfront cost of an electric refrigerator was higher than that of an ice box, running cost was significantly lower. The homemaker no longer need to purchase ice blocks, and they needn’t shop for food every day. They could even go on vacation and return to find most of their food still fresh. Furthermore, electric refrigerators could be placed next to the stove, unlike ice boxes, which were often inconveniently located on back porches where it was cold, leading to kitchen redesigns that saved steps. Refrigerator diagrams in Verna’s booklets showed the best method of storing the foods in different Frigidaire models. Verna helped set their company apart from fierce competition by highlighting the freezer dials and other features that appeared to make Frigidaire indispensable for the modern homemaker. After educating the customers, she informed the Frigidaire sales force so they would understand the customers’ questions. Besides all this, Verna tested new refrigerator models for the company for all kinds of efficiencies.

As a portion of their marketing strategies, refrigerator companies distributed free cookbooks, [reddit] at dealer showrooms. The link takes you to Verna L. Miller’s first cookbook, though co-authored. That 1928 Frigidaire cookbook’s 1st printing was 500,000 copies, running out in 60 days, the 2nd printing was 250,000 copies, and so forth. Their colorful catalogs [reddit] and beautiful booklets represented the epitome of perfect cold storage models.

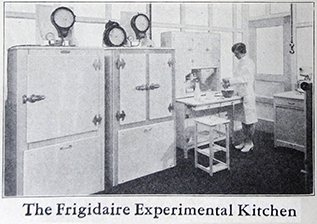

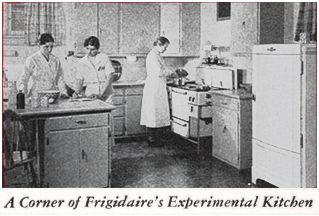

Pictured here is who we believe to be Verna L. Miller in the newly-established 1928 Frigidaire test kitchen. In the next photo, from 1936, Verna Miller is in the middle of a small test kitchen staff. Home Economist Verna constantly tested a whole battery of refrigerators under exacting conditions in the Frigidaire Experimental Kitchen. Frigidaire introduced a clever dial system: similar to regular stove dials, they created freezer dials to use on different recipes. Making Jell-O? Set the dial to high, etc.

Home Economists such as Verna Miller played a crucial role in the early 1900s, as they were the bridge between new manufacturers and women consumers in the new technologies and conveniences. They represented the company with public talks and cooking demonstrations, educating customers while promoting the products, letting homemakers know that it was necessary to change for the sake of convenience. It was work that was particularly suited for women, as most of the changes were in the kitchen where women had reigned for millennia. Verna L. Miller and her staff worked their magic, testing and proving that Frigidaire electric refrigerators were “cool!” in many ways!

Miss Verna L. Miller at Frigidaire

Verna L. Miller perhaps began at General Motors as a armature winder of motors in 1920, then became an office person there, before becoming Home Economist Director of the newly-formed Frigidaire’s Experimental Test Kitchen in 1928. These were the days of life-long work at one company, and Verna was no exception. She rose to such a public role as she was an intelligent and capable woman known for her focused approach and effective methods. She was thin, if not gaunt, looking elegant and pulled together, yet with a big easy smile, even when frowning. She excelled in her prominent public role and skillfully managed a crew of economists at the test kitchen. Verna’s primary objective when developing recipes to homemakers was to minimize food waste through experimentation with the different foods in the home. Verna’s influence reached far beyond the confines of the test kitchen, as she traveled across the United States, delivering educational talks and conducting cooking classes and food demonstrations throughout her tenure as Director. In Oregon, known for its roses, she was given a dinner and awarded an honorary membership in the Mystic Order of the Rose, whatever that was! Her expertise was highly regarded, and she had the honor of teaching at prestigious institutions like Columbia University, which was renowned for nurturing the top future leaders in Home Economics. Additionally, Verna shared her knowledge and passion for refrigeration at various other colleges, perhaps leaving a lasting impact on aspiring home economists.

Verna L. Miller, along with the developments of Frigidaire, branched out beyond refrigeration and dedicated a significant portion of her time to conducting thorough research on electric cookery, home laundering, and various other aspects of homemaking. After World War II, Verna, always keeping up with the times, assumed the responsibility of engaging with customers through color slide films, and took on the role of technical director for up to eight Frigidaire movies, including notable titles like “Grandma Goes to Town” and a Technicolor motion picture called “Frozen Foods.” The media was showcased at clubs, perhaps schools, and any organization which requested it.

Reveries—While Verna continued to give talks and conduct classes beyond1945, it is worth mentioning that during the earlier days of food lectures, 1870s to 1930s, audiences excitedly showed up with pen and paper to take notes on recipes, and newspapers reported the events with detailed descriptions. World War II acted as a dividing line in this regard, and there was a noticeable shift in the level of excitement surrounding these talks. Was it that the people had gone through the Great Depression? Was it the slow inculcation to do less in the kitchen? Was it the reliance on movies and slides during presentations instead of an effervescent lecturer? I’ll put a pin in all that, as I do not know.

Another infatuation with progress was that after WWII women appeared more dreamy-eyed than usual in the advertisements to hear they could simply open a package and turn on the stove to make a full meal. The freezer industry made this possible. Print advertising encouraged the romance with convenience foods for several decades past, making it challenging to determine the exact catalyst…. Yet, with women increasingly joining the workforce after WWII while raising “baby boomer” children, women knew that the responsibility of cooking daily meals rested solely on their shoulders. Perhaps it was overwhelming–you think?– and without hired housekeepers simplified homemaking tasks was required.

Long gone were the days when a housekeeper boarded at the home to assist. – link to Cottage Life.

Regardless of the plusses and minuses of frozen convenience foods, metal was needed during WWII for the war, and the War Production Board prohibited the manufacturing of refrigerators. After the war, Frigidaire campaigned to win a potential 2 million food locker customers by manufacturing Frigidaire home freezer units.

The food locker business began during the ice box days, 1905, when people needed storage for excess butchered meats or the garden’s overflow in a refrigerated storehouse. By 1946 there were 6,000 of these locker businesses in the US. Now the term food locker is changing and rarely do rentable food lockers exist, except in remote rural areas. Besides the sales force and magazine ads, two of Frigidaire’s major strategies of attaining the new home freezer market was via public talks by Verna and making educational movies which were distributed to clubs, schools, etc.

Verna L. Miller, Life Story

Verna was born on Mar 28 1898, second child to Clifford W. Miller and mother Grace [Snell] Miller. Verna’s parents married as young 20-year-olds on November 7, 1894, in Miami county, Ohio. In 1900 Verna’s father Clifford was a Teamster out of Springfield, Ohio, and the family included an additional newborn girl, and a 16-year old housekeeping boarder. By 1910 the family increased with more daughters to equal a family of one son, the eldest, and five girls living in Bethel, Ohio, as the father switched to farming. It was disclosed later that during this time the tall medium build father, Clifford, was physically abusive. In 1916 the family increased to six girls. In 1918 the family was still together but we discovered that in addition to being physically abusive the father would not provide for his family, although later it was said that he was able. Verna’s mother Grace, driven by her determination to protect her children from the father’s cruelty and neglect, decided to leave him behind in 1920. She relocated with all seven children to Dayton, Ohio, where they rented a house at 66 Hallwood Ave, while the father remained isolated as a farmer in Bethel.

Dayton was considered the Silicon Valley of its age, as the cash register, the airplane, and self-starting ignition for automobiles were invented there. When first arriving, Verna, 21, became an armature winder at a factory where electrical fitters repaired or replaced broken parts of electric motors. This in fact could have been at General Motors, working there before transferring to their Frigidaire division. Her older brother Howard became a machinist at Cash Register, and sister Glenna was a packer at the cracker company, probably Green & Green Company who made graham crackers and developed the Cheez-It cracker a year later. The mother and rest of the family in Dayton may have relied on those three incomes until the others were old enough to work.

Verna’s parents divorced by 1923 and Clifford married again. The second wife filed for divorce after nine years and three children, citing the same reasons as the first wife, gross neglect and extreme cruelty. In 1929 when the Great Depression hit, banks foreclosed on the father’s property and by 1930, age 55, he was a prisoner at Clark County Jail, Springfield, Ohio. For some reason the second divorce wasn’t finalized and in 1936 it appears as if the wife asked for a dismissal of the case, and it was granted. This same year Clifford sued someone regarding a mortgage on his old farm. The second wife and he didn’t live together, as in 1940 Clifford was listed in the census as living with a woman who said she was his wife, yet the 3rd marriage certificate was dated in 1943 three years later. He died in 1945.

With a solid and dynamic career, and the ability to financially care for her mother, Verna needn’t look back. She never married, which allowed her to commit more fully to her professional life. All but one of the other sisters married, two of them marrying as late as 1940, yet staying all together until then.

Accompanied by her mother and a few of her sisters, they relocated to at least two different rental properties over the decades. One of these rentals was a house located at 635 Foreal Avenue in Dayton in 1930, while the other was an attractive 1915 two-family gambrel-roofed house with a porch situated at 923 Lexington Ave [google map 71 yrs later] in 1940. During this time, Verna held the position of Director of Home Economics, while her sister Esther worked as a Stenographer for Auto Sales and Mabel served as a Secretary for Beauty Supply. It is worth noting that in 1940, the year two of the sisters married, Verna’s sister Geneva, at the age of 39, was committed as a patient to the Institution for the feeble-minded in Scioto Township, Ohio. It is uncertain whether her condition was due to being feeble-minded or if it could be attributed to the early exposure to violence. Additionally, during this period, individuals could be committed for exhibiting a lack of productivity or other behaviors considered regressive. However, the exact circumstances remain unknown.

In 1956 Verna transitioned from Frigidaire’s Home Economist Director to handling customer relations in the merchandising department, possibly indicating a shift towards semi-retirement after 28 years as Home Economist Director at Frigidaire. Considering her age of 58 when she switched positions, her career at Frigidaire would have exceeded 30 years if she retired at 65, reaching into the early 1960s. If we are to assume her armature winder of motors job in 1920 was at General Motors (GM), which is likely, before moving to GM Frigidaire, she was at GM for 4 decades.

Verna’s mother Gracie died in 1960. Verna retired in the early 1960s, and her own armature stopped in March 1981 at 82 years.

Frigidaire Books, Booklets & Catalogs

These publications range from the beginning of Frigidaire to before 1960 during Verna L. Miller’s term as Director. There were earlier booklets, undated, just called “Frigidaire.”

- 1927 Frigidaire Frozen Delights by Jessie M. DeBoth

- 1927 Frozen Desserts and Salads made in Frigidaire by Jessie M. DeBoth

- 1928 Frigidaire Recipes by Miss Verna L. Miller, Home Economist of Frigidaire Corporation, Jessie M. DeBoth, A. B. Director of DeBoth Home Makers’ Schools of Chicago, Illinois, and Alice M. McCarren, Director of Home Economics Division, Westinghouse.*

- 1929 Handbook on Food Handling in the Home

- 1929 Frigidaire Automatic Refrigeration, refrigerator color catalog

- 1930 Frigidaire Frozen Desserts

- 1930 Frigidaire Salad Book

- 1930s Frozen Desserts and Salads made in Frigidaire

- 1931 Frigidaire Advanced Refrigeration [internet archive]

- 1931, 1932 Frigidaire Recipe Book

- 1933 The Frigidaire Key to Meal Planning: A new program of menus for greater convenience, variety, dietetic balance, economy Based on Studies made by Miss Verna L. Miller, Director of Frigidaire Home Economics, with the assistance of Mrs. Alta Bolender Hirsch, Director of Dietetics, Miami Valley Hospital, Dayton, Ohio

- 1931, 1938, 1939 [with interior pic of test kitchen], 1940 Your Frigidaire Recipes

- 1934 Aboard the Seth Parker [Gloucester Fisherman type on cover]

- 1933 [side of face, front of fridge on cover] 1934 Your Frigidaire Recipes and Other Helpful Information [dessert setting on cover]

- 1936, 1937 Your Frigidaire Recipes [fabric weave photo with red title on cover]

- 1936 Famous Dishes From Ever State

- 1943 Wartime Suggestions to help you get the most out of your Refrigerator

- 1944 101 Refrigerator Helps

- 1949 Grandma’s Favorite Recipes

- 1949, 1955 The New Thrills Of Freezing With Your Frigidaire Food Freezer

- 1951 Fruits and Vegetables: How to Choose

- 1951 Better Foods For Less Money

- 1951 All About Meat

- 1954 Getting to Know Your New Frigidaire Imperial Cold-Pantry

- 1958 Food Freezing…the way to real Carefree Cooking

- 1958 Freezing is Fun with a Frigidaire Food Freezer

- 1958 Frigidaire appliances : presenting golden anniversary models celebrating 50 years of General Motors leadership

I have not included Frigidaire booklets that were included with the new appliance, “How to Use and Enjoy Your New Frigidaire…” although they’re delightful; nor the booklets for products other than refrigerators, such as stoves, and this list stops before 1960, when Verna stepped down. So there’s no “Bewitched” stoves! And how do I break the news to you that I found an X-rated comic book from 1930s called “The Frigidaire Salesman?” But here’s an oddly entertaining official advertising film from 1956 [internet archive]. There are other Frigidaire TV ads there.

*Miss Verna L. Miller’s first book, Frigidaire Recipes was co-authored by Jessie M. DeBoth, A. B. Director of DeBoth Home Makers’ Schools of Chicago, Illinois and Alice M. McCarren, Director of Home Economics Division, Westinghouse [two years later Westinghouse debuted their first refrigerator!] The book contained over 100 well-tested recipes specific to cooling and freezing, including specialty ice cubes.

From the Soapbox: I’m still trying to put this time period in perspective for myself! During the period spanning from the 1910s to the 1940s, there arose a growing necessity to establish a connection between manufacturers and women who, prior to their exposure to new ways, possessed a heritage of tending gardens and crafting everything from scratch. These women relied on their gardens, wells, ice boxes or root cellars, wood-burning stoves, and often many contributing children and paid boarders. Around 1900, and gaining momentum in the 1910s, a significant number of women underwent training to become home economists, dieticians, domestic scientists, cooking instructors, lecturers, test kitchen directors, and consumer service directors. Their purpose was to bridge the gap between the new Industrial Revolution food industry manufacturers and women homemakers. However, 50 years later, following World War II, the home economists weren’t needed as much, as the new markets were now established markets, and new advertising methods emerged. The focus of encouraging homemakers to rely on easier and easier prepared foods requiring less and less effort continued, and was greatly enhanced by good refrigeration. From the 1800s to the 1930s the titles “Domestic Scientist” and “Home Economist” meant a progressive and intelligent woman, in high demand by manufacturers. By the 1970s the same titles became a joke. Many ‘elders’ today remember the “Home Economic” classes in high school circa 1970s. They were taught without excitement or glamour, a perfunctory class from days gone by. In the name of cultural liberation, women were discouraged from cooking, allowing the now-secure food companies to manufacture convenient family meals, for better and for worse. The good news is that progressively other professions opened for women.